For the inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro who are not part of the bourgeoisie and whose reality unfolds in the adjacent favelas, funk signifies not only a music genre, but also a dance, a beat, and a way of talking about hardship.

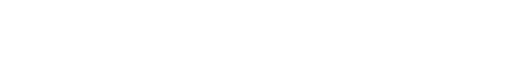

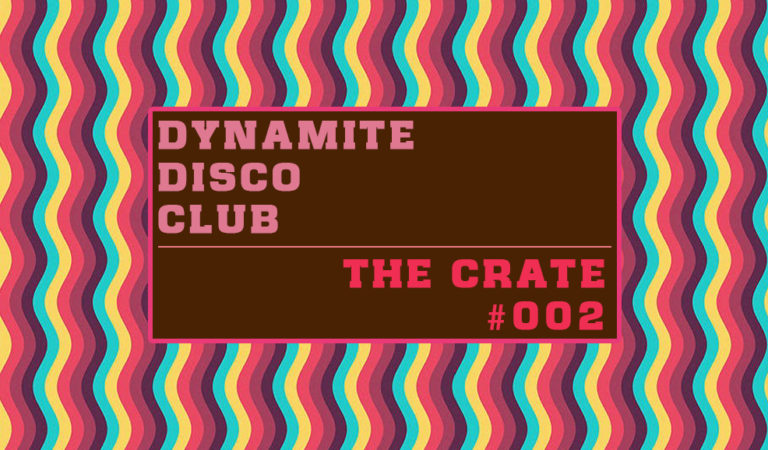

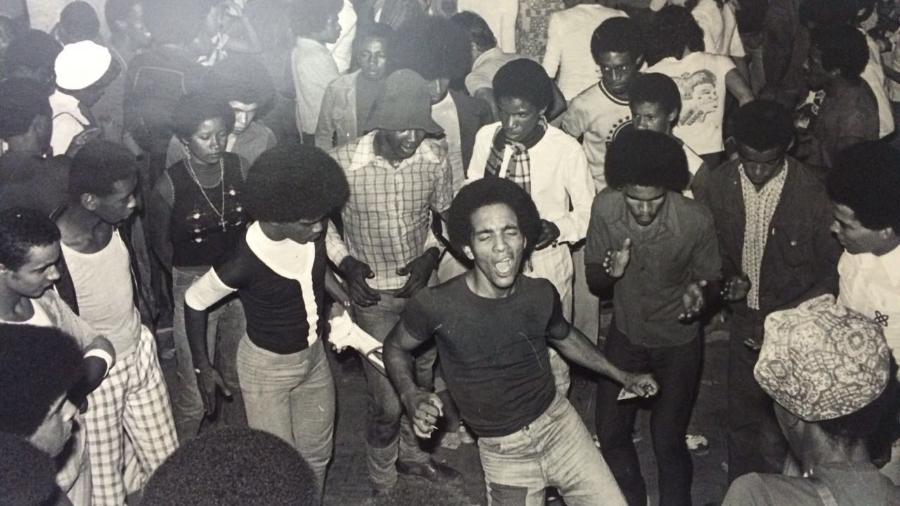

The history of funk in Brazil began in 1970, driven by the explosion of the Black Power movement in the United States and the arrival of imported soul records brought by collectors and Black music enthusiasts who travelled abroad—something still largely inaccessible at the time for most Brazilians. Promoted by radio announcer Big Boy and DJ Ademir Lemos, the Baile Blacks or Bailes da Pesada were parties that served as a symbol of musical and aesthetic resistance, connecting these imports with their eager new audience.

Brazilian Funk, a.k.a carioca within its country of origin, is a genre of dance music similar to and derived from Miami bass. Records were brought back from America, played in clubs and then sampled in contemporary underground mixes with undertones of Afro-Brazilian sounds, all while retaining one of the umbrella terms for this type of music: funk.

Funk was introduced to Rio de Janeiro as a vehicle for racial consciousness, encouraging Afro-Brazilians to embrace their heritage in the face of a society dominated by drug trafficking, unemployment, and lack of healthcare. In no other music genre is there such an aggressive assertion of sexuality, masculinity, oppression, poverty and law-defying uprising. This is then counter-balanced by a humbling presence of lyrics focusing on black pride, dignity in the face of injustice and feminism.

The genre is the loyal output of a country whose society has been composed by an intense historical process of cultural amalgamation from different parts of the world. Rio funk carries discrimination and struggle in its genome—a rhythm that came from the slums, from Black and marginalized bodies, and year after year, still surprises us with its inexhaustible capacity to be reinvented. It represents the absolute freedom of expression of a people who are economically oppressed. By acting as a product of resistance against the dominance of the music industry, funk carioca has become an example that others can look to for inspiration. It continues to converge with new trends and social issues in Brazil and beyond, attracting an increasingly larger and more diverse audience, and influencing artists like Madonna, Drake, Bjork, J Balvin, Diplo and M.I.A.

Criminalisation of Brazil’s Vibrant Funk Scene

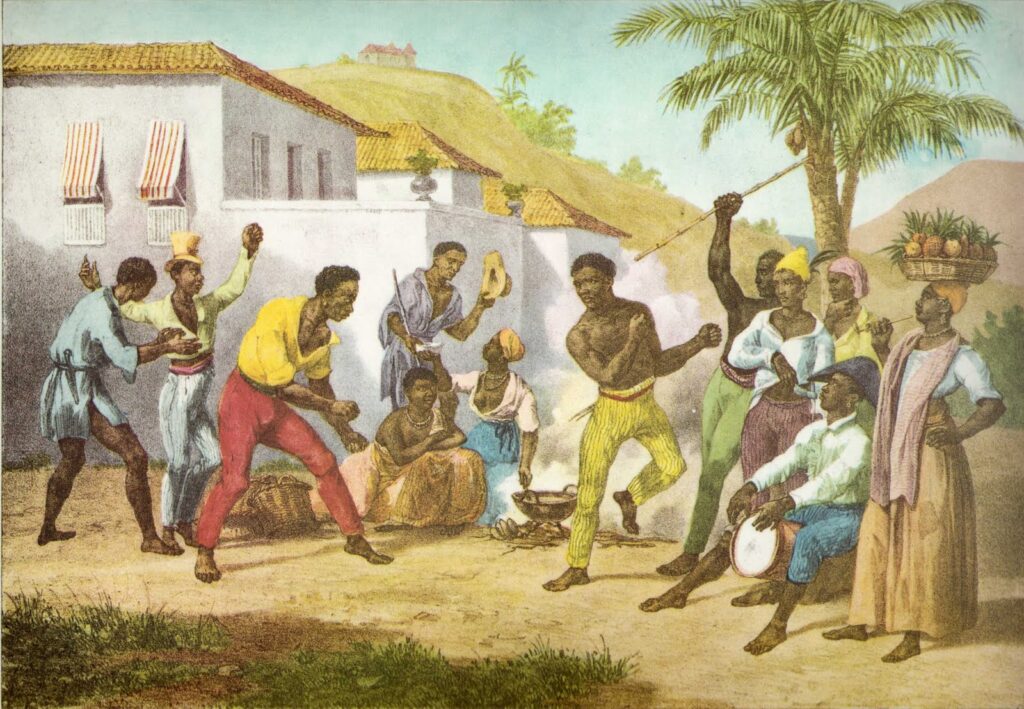

There’s no way to understand funk without seeking the roots of another Brazilian genre and culture. Samba emerged in the period immediately after the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888, and was strongly associated with the marginalised Black population. Thousands of freed Black people built their homes outside the cities, in what became known as the favelas, and samba is indigenous to those communities. Almost predictably, samba was quickly frowned upon by the contemporary Brazilian, largely white, elites.

Samba and funk have two main elements in common. There’s social revolt and sometimes even praise for crime. There’s also social elevation, a way for artists to use music as an attempt to integrate and succeed. Samba and funk represent “the aspirations of the Black population to integrate into a wider Brazilian society, intending to overcome this marginalisation.”

The criminalization of these genres was always attributed to racial and socio-economic issues that arose as a result of the state’s refusal to recognize these communities. The criminalization of baile funk is a pattern the Brazilian government has repeated with other Afro-Brazilian forms of art, such as samba and capoeira.

After the dictatorship ended in ‘85, façoes, or drug cartels, began taking over everything – even baile funk. So if someone wanted to buy drugs, they’d go to baile funk parties to get them. But people didn’t really give credit to the political and social changes the cartels were making at the time. While the government completely ignored favelas and suburbios, traffickers were creating schools and bringing cleaner water into the slums. Funkeiros were creating music with a subtle political message, a language only those on the margins could understand.

With police shutting down shows and the government passing laws banning the music and parties in the early 2000s, criminalization transformed from social to legal rejection. In 2000, Law 1392 created obstacles for the organization of baile funk parties in favelas. Organizers faced a slew of bureaucratic tasks and were forced to disclose every detail to the authorities before the event occurred. This type of surveillance allowed the police and military to take over the parties. In Rio, the military and police have a reputation for discriminating and even murdering black and brown poor Brazilians in favelas. The government only started protecting the baile funk movement in 2009, when Law 5543 was passed to prohibit any discrimination or prejudice against the genre.

With artists from Brazil and other countries adopting the sound and promoting it, funk seems less subject to stray bullets that seek their targets in the informal economy of the favela. But the favela itself continues to fight for rights and recognition. As criminalization seems to rise with huge events, such as the 2014 World Cup and 2016 World Olympics, how funkeiros and the baile funk movement will respond remains to be seen.